Age:

High School

Reading Level: 2.2

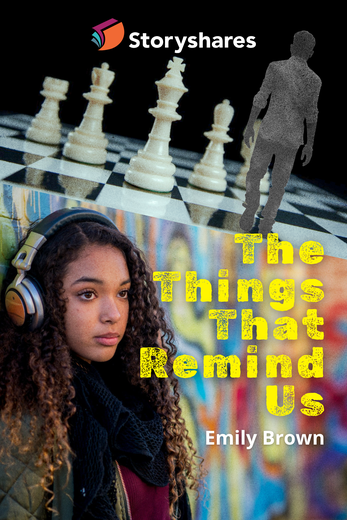

Chapter One: Socks

There are certain things that people just don't talk about.

People don't talk about it when your socks have holes in them. It would be rude if they did. No one likes being rude.

Amy and Nat know this. It's why we don't talk about my dad.

They are my best friends, and have been since third grade. Now we are fifteen, and we are still best friends. They know everything about me, and I know everything about them.

They know that my parents had a divorce, and now my dad is gone. He left.

They don't know where he is. I don't know either.

We sit on the steps outside school and wait for our parents to pick us up. My mom is usually late. But she doesn't like me to take the bus, so I have to wait.

Nat is the chatty one. Now she is talking about a time when we were ten, and I invited them to my house for a sleepover.

"I knew we were best friends when you invited us that time," she says. "I knew we always would be! Remember those cookies your mom made for us? Deeee-licious! And your dad made up that game where—"

She pauses. She's just realized that she's not supposed to talk about him.

Amy changes the topic. "Or, Nat, Lucy, do remember when that crow stole my hamburger? How funny was that?"

She and Nat start talking about the crow. I'm still thinking about my dad.

My dad has become like socks with holes in them. No one talks about him anymore, just like no one talks about those socks. Even if they were your favorite socks, people still wouldn't talk about them.

I wish they would.

Chapter Two: Rocks

When Mom picks me up, she looks tired. The twins are arguing in the back seat of the car. I would be tired too.

Since Dad left, they never stop arguing. It's their new favorite thing.

I want to tell Mom that I miss Dad, because I don't think she knows. But I don't want her to think I'm mad at her because he left. So I don't say anything.

I keep the words inside me, where they feel heavy, like a rock that I have to carry around with me. A big, heavy rock.

Before Dad left, Mom would have asked how Amy and Nat are doing. She would have asked what I did at school today, and how my day went.

Now we just sit quietly, waiting to get back home.

The twins argue the whole way back.

When we get out of the car, Mom says, "Danny, Regan, please go clean up your room? It's a mess. We need to finish with all of our rooms so we can start clearing out the spare room."

The spare room is where Mom put all of Dad's things when he left.

The imaginary rock grows a little bit heavier.

All of the things in the spare room are memories. Dad's old, squeaky armchair, where he used to read to us. Dad's laptop, the one he was building. Dad's DVD collection of all his favorite movies. We had only watched half of them together.

Mom wants to throw them all out. She says we don't need them.

It's true that we don't need them. But it feels like she is planning to throw every piece of Dad out too, until we aren't allowed to remember him at all.

"Lucy, can you clean up your room too?" Mom asks. "I know it's already pretty clean, so when you're done there, you can get started on the spare room. I have some groceries to unpack."

She leaves to unpack her shopping, and I carry my imaginary rock up the stairs to my room.

Chapter Three: Chess

I finish cleaning my room quickly.

I want to start my homework, but Mom asked me to start tidying up the spare room. She has left a trash bag hanging on the door handle, with a sticky note that says: Throw out anything we won't use. Thanks Lucy! Love, Mom.

I don't want to throw anything out at all!

But I go into the spare room anyway.

There are a lot of boxes, and plastic containers with Dad written on them in big, black letters. But there is a lot of garbage, too. Old packaging and old receipts that Dad kept, and random pieces of paper.

I can start with the garbage.

The papers go into the trash bag. The receipts do too, and the old packaging. Crunch, crunch. The papers crunch as they are shoved into a bag together.

Suddenly, I see something. Under a pile of old papers, there is a small, black box.

I pick it up.

It's Dad's miniature chess set. The tiny chess pieces are hidden inside. When the box folds out, the inside of it becomes a chess board. It's about as big as my two hands put together.

Dad taught me to play chess. He said I was a natural at it—I almost always won.

I don't think I'll ever play chess with him again.

Mom would tell me to throw it out. Dad was the only other person in our family who played chess. Now that he's gone, no one will use it.

But this is a memory I'm too scared to lose.

I hurry over to my room and hide the chess set under my bed.