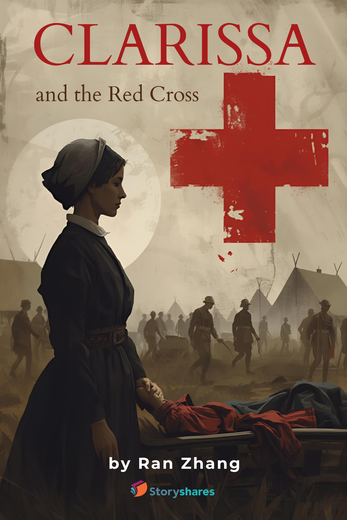

Age:

High School

Reading Level: 11.3

Chapter One

It is unlikely that anyone has not heard of the Red Cross. But the founder of this important humanitarian organization is often overshadowed by the charity itself. Few are aware that the founder of the Red Cross was a woman.

This is the story of that remarkable woman and her often-overlooked name: Clarissa “Clara” Harlowe Barton.

Born in North Oxford, Massachusetts, Clarissa (or Clara, as she is commonly known) was heavily influenced by her father’s progressive ideals and patriotism. Captain Stephen Barton was a selectman and member of the local militia involved in the removal of Indigenous populations in the northwestern USA. He was also a strong advocate for humanitarianism and a local leader in promoting those beliefs. Clara would later reflect on her actions, saying, “The patriot blood of my father was warm in my veins.”

Growing up in a small farming community, Clara Barton had no formal medical training. She began attending school at the tender age of three and was a shy but diligent student. Perhaps foreshadowing her future work, Clara cared for her younger brother David after he had a severe head injury, administering bloodletting and medication, which likely contributed to his recovery.

Contrary to the typical image of a leader or achiever, Clara was neither outgoing nor confident. Her introverted and meek nature made it difficult for her to make friends at school. Her shyness eventually kept her from completing her enrollment at Colonel Stones High School, manifesting as a crippling lack of appetite and social anxiety.

Ultimately, Clara returned home after her anxiety became too overwhelming for her to continue at school.

Clara Barton always found herself more at ease with her male cousins than her female ones, happily mingling with them. Her tomboyish antics eventually led to a horse-riding accident, prompting her mother to encourage the development of her femininity. Consequently, a female cousin tutored Clara in skills like needlework.

Though Clara became more involved in traditionally feminine activities, she had a strong fear of becoming a burden to her family. Despite her shy nature, she wanted independence rather than being confined to a domestic life.

Persuaded by her parents, Clara went back to school, this time at the Clinton Liberal Institute. She planned to earn a teaching certificate. It appears that her break from school had been helpful, as Clara excelled academically, just as she had in her early years. She received her teaching certificate at the age of seventeen, marking the beginning of her professional life, not in medical care but in education.

Chapter Two

Clara Barton excelled as a teacher, but life had more in store for her. After about a dozen years of teaching, she had taught many students with whom she maintained contact throughout their lives. Unlike her high school experience, she was able to make many friends.

Along with a female friend, Barton opened a free public school in neighboring Bordentown. Both women earned good wages, and the town felt compelled to raise over $4,000 in light of their accomplishments for a new school building.

However, Barton soon faced challenges due to her gender. She was demoted from her role as principal and made a “female assistant” because she was deemed unfit for the rank as a woman. This was a heavy blow to Barton, and her old anxieties resurfaced. Aggravated by the harsh working environment, she suffered a nervous breakdown and quit.

Barton was not content to be subordinate to men on account of her gender, or to receive less pay. She famously declared, “I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”

Determined not to remain jobless, Barton moved to Washington D.C. in 1855 and became a government clerk. However, the rampant sexism that affected her previous work followed her. She again faced abuse, discrimination, and slander from her male coworkers. The male clerks were angry at her for earning the same salary as a man, as she was the first woman to do so in such a position. Barton was demoted once again, this time from a clerk to a copyist.

This was far from the end of Barton’s problems. She was eventually fired by Democratic President James Buchanan for her Republicanism in 1858 and was only rehired three years later by President Abraham Lincoln.

Chapter Three

Clara Barton’s opportunity to prove herself came with the era of the American Civil War.

True to her humanitarian spirit, Barton helped both Union and Confederate soldiers by providing medical care, food, and clothing supplies, as well as helping recover soldiers’ lost belongings. She gained permission to pass through battle lines to carry out her work and search for missing persons as needed. Although she was firmly under the employment of Union leader Abraham Lincoln, she traveled with the army as far south as Charleston, South Carolina.

In a letter to the Governor of Massachusetts, Barton wrote, “I ask neither pay nor raise, simply a soldier’s fare and the sanction of your Excellency to go and do with my might, whatever my hands can find to do.” She also expressed her commitment, saying, “I shall remain here while anyone remains, and do whatever comes to my hand. I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them.”

In June of 1864, Barton was appointed superintendent of nurses for the Army of the James. She helped Black soldiers of the 45th Massachusetts Regiment during their attack on Fort Wagner. At the personal request of Abraham Lincoln, Barton established a bureau of records to search for missing men, answering the pleas of thousands of worried relatives.

She found many of her former pupils fighting for the Union and expressed her pride, saying, “I am glad to know that somewhere they have learned their duty to their country, and have come up neither cowards nor traitors.” Barton also showed her affection for her students: “You know how foolishly tender my friendships are, and how I loved ‘my boys.’”

Barton was not only caring and gentle toward her former students but also toward all soldiers. She took the time to read to them, talk to them, write letters to their families, and do her best to support them and keep their morale high.